Picture the scene: a Saturday morning in the spring of 1977. A detached house in Forest Gate, a suburb of north east London. Inside, 16-year-old James Caan (born Nazim Khan) shuts the door to his bedroom, decorated with posters of his beloved Chelsea FC, for the last time.

Heart pounding, a huge lump in his throat, he enters the drawing room where his father, Abdul Rashid Khan, is getting ready for work. ‘Can I have a word Dad?’ His father nods. ‘I don’t want to join the family business. I want to do my own thing. And I’m moving out…’

Fast forward 32 years. James Caan, 48, is sat behind his desk, framed by huge Georgian windows. Sunshine pours into his office in a converted Mayfair townhouse. The 16-year-old boy who left home with £30 in a Post Office savings book, and a month’s deposit on a small Kensington bedsit, is a hugely successful entrepreneur worth millions – 65 of them. He has a beautiful wife, Aisha, 50, a fashion designer and artist, and two lovely grown-up daughters Jemma, 22, and Hanah, 21. He owns homes around the world, including one in Cannes on the French Riviera, and one in Lahore, Pakistan, where he was born. He has the requisite millionaires’ toys: the cars – the Maybach and Elton John’s old Aston Martin Vantage Volante; the sleek yacht moored in the Med; and, perhaps his most cherished possession of all, Wembley season tickets. So how did James turn things around?

Risky business

Quiz James about his approach to business, he’ll tell you that, ‘To this day my biggest drive is my fear of failure.’ He’ll also tell you that, unlike many entrepreneurs who are very risk tolerant, he’s not one of them. ‘A big part of my career has been about risk management,’ he says. ‘I have always considered the odds and the options, and it’s only when I’ve calculated that the risk is minor, or non-existent, that I’ve pushed things forward. Normally, in these circumstances I ask myself, what’s the worst that could happen?

Arguably, the biggest risk James ever took with his career was leaving home at 16, with no qualifications. In the top stream at school, had he delayed his departure until the summer, he would probably have picked up an O Level or two for his CV. Instead, he dropped out of school as soon as it was legally possible for him to leave, with dreams of founding his own business. ‘As far back as I can remember, it was always my passion to be an entrepreneur, like my dad, who ran a business that manufactured leather garments. At the age of 12, I started buying bomber jackets from him, wholesale, and selling them to mates. In those days, I would get £3 a week pocket money and I’d make £5 selling one jacket! Dad loved that I had a talent for business. He was adamant that I would join the family business and it wasn’t up for debate. His view was that I’d go to university, come out of university and join him. I felt quite pressurised by that. Because something you’ve grown up with, that you’ve seen every day of your life, clearly doesn’t have the same appeal as something you might want to do yourself.’

But even at that young age (even before he even knew the meaning of the term, risk tolerance), James had weighed up the odds and his options. What’s the worst that could happen? If he failed, he reasoned, he could take the job his dad had lined up for him in the family business.

‘In my head, if I was going to have to join the family business anyway, I had a choice: go to university first and then join the family business or use the five years from 16 to 21 to find out for myself if I’d be better off doing something else.’

It was an argument his father had to accept. After all, wasn’t his son simply taking his advice, to ‘observe the masses and do the opposite’?

But there was an element of risk left unspoken: failure wasn’t an option. Failure meant giving his dad a chance to say, I told you so. ‘Also, subconsciously, because I’d left home, I felt I had to make it,’ says James. ‘Deep inside there was a determination, an absolute drive that whatever I was going to do was going to work. I needed money to pay the rent and it really didn’t matter what job I did, so I took the first one I saw – a sales rep. A year later, James stumbled into secretarial recruitment as a trainee interviewer for Premier Personnel in Holborn. ‘Two things appealed to me about the work: the idea of sitting in an office interviewing somebody sounded quite sophisticated. I also liked the fact that you got paid a percentage for everybody you placed – the idea that if you worked hard you could earn more felt quite exciting.

‘Within three months I’d doubled my earnings, and my commission was twice my salary. I loved the job.’ A year later he’d moved to the City Centre Staff Bureau. Then he was headhunted by Alfred Marks recruitment agency, before settling down in the recruitment department of a financial services company called Reid Trevena. It’s here he met his future wife, Aisha.

She first surprised him by refusing to take a job at Reid Trevena. A graduate of the London College of Fashion, she’d decided to pursue her dream of opening a fashion boutique. Keen to impress her, James offered to back her business. ‘It was a great line and seemed like the right thing to say at the time.’ Never thinking there was any mileage in it, Aisha surprised him again and got the business. Forced to make good on his word he raised the money by taking out out three £10k overdrafts on three gold credit cards!

Building the business

In 1985, aged 25, after several years of backing Aisha’s successful boutiques, James decided to set up a recruitment agency – Alexander Mann. For months he worked out of what was little more than a broom cupboard with the Pall Mall address he felt was essential for the company’s image. Again, his father’s advice would be invaluable. Alexander Mann, James decided, would fill the hole in the market for a mid-level headhunting firm. Success. Within seven years it was turning over £130-150 million.

In 1993, James’ second venture was the executive headhunting firm, Humana International, co-founded with his partner Doug Bugie. In six years, it grew to 147 offices in 30 countries. By 2004, he had sold Alexander Mann and Humana. The proceeds from the businesses probably netted him close on £100 million. Cash.

The gap year

The gap year

So at the relatively young age of 42, James called it a day. ‘I’d done my bit. I’d been working pretty hard since the age of 16.

Quite unusually, money was not an object, and in my head I’m thinking, I’m having a gap year. I can do what I want. It was a year that began with him casting off his work suits and developing a taste for ripped Calvin Klein jeans. It was a year in which he grew a beard, let his hair grow longer and started wearing beads and flip flops. It was a year in which he learned to fly planes: ‘But it didn’t give me the thrill I thought it would.’ Then helicopters: ‘Much better, much more exhilarating.’ Then he learned to sail a yacht. ‘And this is where I find the thing that really gets to me. I love the sea, I love the adrenalin. So I buy myself a yacht (as you do).’

Eighteen months into his gap year, and a Harvard MBA later, a chance meeting with a friend just back from Lahore in Pakistan had James flying out to his birth city the next day. ‘When I get there I’m really taken in by the poverty, the lack of education. As I travel around, I start to feel emotional. I’m in a village called Hare, just outside Lahore, and looking around I’m amazed by how primitive it is. People are still living in shacks, they’ve got no running water and no continuous electricity – it’s very basic. But more heartbreaking is that there’s no school in the entire village. And I thought, I’d love to build a school and name it after my father.’

His friends in Pakistan thought he was barmy. But within two years the Abdul Rashid Khan Campus for kids aged five to 11 was up and running. ‘It is probably the most satisfying thing that I’ve ever done,’ says James. ‘I fund it entirely myself. I paid for the land and the construction. I pay for the teachers, the uniforms, the minibuses to pick up the kids and drop them off.’

Because the school is free, there’s a strict admissions criteria based on need, not means. ‘I’m only interested in people who cannot afford it,’ he says. ‘Those that have the means don’t need me.’ Would he consider allocating a few places to those who could afford to pay? ‘No. I have a very clear mandate: the objective is to make a difference. I’m not selling education.

‘I visit the school every six to eight weeks and I spend two or three days there. I know the teachers very well, I know the kids quite well. My daughters go there to get a sense that the grass is not always greener on the other side; to know what it’s like not to have anything. This October we’re going back to buy the adjacent land to build a secondary school.

Towards the end of the millennium, during the Kosovan crisis, James had flown out to the province with the musician Cat Stevens, now known as Yusuf Islam. ‘We came across a village with 600 kids orphaned because of the war. They had nothing. Literally nothing. I decided to support the people of the village until aid reached them, not with blankets or clothes, but by giving them a financial allowance to give them their dignity back.

James’ response to the 2005 Kashmir earthquake was equally hands on. ‘I flew out to Kashmir. All the aid was focused on the flat lands because it was quite easy to put tents there, but in the mountainous terrain it was just too hard. I remember speaking to an army general and asking what happened to the people up there? The look on his face said, they die. I was just choked. The problem, I discovered, was that for the people living in those areas, the land is their life and they’re never going to give up a piece. So, frankly, they’d rather live there regardless of the catastrophic consequences, even though the government was urging them to return to the safety of flat lands.

‘I wanted to do more than just donate tents, and came up with a plan to build 100 homes. I returned to England, clueless as to how I’d get the houses built. A friend suggested I call a structural engineering company called Buro Happold. They’d just spent six months redeveloping an entire area after the Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004, and knew exactly what the issues were. So I hired them. The architects went to Kashmir, surveyed the land, came back and drew up the designs; the houses had to be earthquake proof and the roofs had to be able to withstand several feet of snow. I then went back to Pakistan to find a factory that could physically make 100 houses. I organised the transport to get the houses shipped to the region, the 4x4s and mules to get them up the mountain, and roped in the army to help build them on-site.

‘It was a nightmare. I can’t begin to tell you. Making the statement was easy; the challenge of getting it done was something else. And when the houses turned up, they couldn’t cope with the snow; the testing of the roof hadn’t quite worked. So I sent them all back. Eventually, when they were complete, I flew back to Kashmir to meet with the people to whom I had donated the houses – what a life-changing event. [Each] experience really moves me. The journey of giving something back, making a difference to somebody’s life, is more rewarding than business. This has given me a better sense of achievement and adrenalin than I had ever thought existed. The only thing I’d known was that you build a business, become successful, make money, do the next deal – you’re always on this chase. And suddenly I stumble on something that starts to mean more to me.

‘Since I sold the business, about a third of my time is spent on focused projects of this nature. I do a lot of work with the Prince’s Trust. Again it’s very me, it’s entrepreneurial, it’s giving somebody a chance, it’s making a difference. I also do quite a bit of work with the NSPCC.’

Back in business

In 2004, James launched his private equity company Hamilton Bradshaw as a vehicle to reinvest the cash he made from the sale of Alexander Mann and Humana. Today, Hamilton Bradshaw owns 40 businesses across all industry sectors, with a turnover of £400 million. So how has he fared in the recession? ‘No matter what you do or who you are, we are all affected by an economic slow down. No question. But because I invest my own money and my business is buying companies, it’s quite an interesting time because valuations are much lower. If you’re brave enough, this is a great time for investing. So I continue to invest quite aggressively.’

In 2004, James launched his private equity company Hamilton Bradshaw as a vehicle to reinvest the cash he made from the sale of Alexander Mann and Humana. Today, Hamilton Bradshaw owns 40 businesses across all industry sectors, with a turnover of £400 million. So how has he fared in the recession? ‘No matter what you do or who you are, we are all affected by an economic slow down. No question. But because I invest my own money and my business is buying companies, it’s quite an interesting time because valuations are much lower. If you’re brave enough, this is a great time for investing. So I continue to invest quite aggressively.’

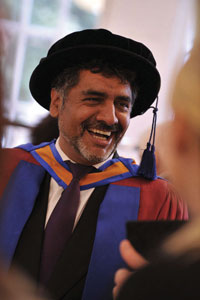

There’s no doubt that the boy who left home with the hope of making something of himself has, in wildly surpassing his dreams, achieved something very special. Earlier this year he was appointed co-chair of the government’s Ethnic Minorities Task Force. He’s the business ambassador for the 2012 Olympics, and his seat on the BBC hit show Dragons’ Den has catapulted him to celebrity status. He’s even received an honorary doctorate from Leeds University. ‘It’s really funny,’ he says. ‘A few weeks ago, the whole family graduated in the same week. Hanah graduated from LSE on the Tuesday. On Wednesday, Aisha got her masters from St Martins School of Art. On Thursday Jemma graduated from UCL. When we got up on Friday, Hanah said, “Dad, it’s not fair. I’ve bust a gut to get my degree. You left school at 16 and now you’re the most educated in the family, with a PhD in Business”.’

So what’s next for James? ‘More of the same. I love what I do. I’m really happy with what I do, so why change a winning formula?’ And, of course, now that he has those season tickets, he can spend time with Aisha watching World Cup qualifiers at Wembley.